This thirty-sixth episode of the Philosophy Bakes Bread radio show and podcast features an interview with Cole Nasrallah, talking with co-hosts Eric Weber and Anthony Cashio about the paper that she gave at the Future of Philosophical Practice seminar at the University of North Carolina Asheville in July of 2017. Cole’s paper was on “The Elements of High Value Philosophy and Audience Accessibility.”

Cole is a philosopher, an author, and a teacher, as well as an artist and photographer. She teaches philosophy at a private girls academy and at the College of Southern Nevada in Las Vegas, Nevada. Cole has written for the public, studied bioethics, and has been a professional photographer. She has a knack for speaking and writing in accessible and clever ways. For one example, in this interview, she explains that “YOLO,” which stands for “You only live once,” is “the poor man’s carpe diem!” We had a great time talking with Cole in Asheville and since then on social media.

Listen for our “You Tell Me!” questions and for some jokes in one of our concluding segments, called “Philosophunnies.” Reach out to us on Facebook @PhilosophyBakesBread and on Twitter @PhilosophyBB; email us at philosophybakesbread@gmail.com; or call and record a voicemail that we play on the show, at 859.257.1849. Philosophy Bakes Bread is a production of the Society of Philosophers in America (SOPHIA). Check us out online at PhilosophyBakesBread.com and check out SOPHIA at PhilosophersInAmerica.com.

(58 mins)

Click here for a list of all the episodes of Philosophy Bakes Bread.

Subscribe to the podcast!

We’re on iTunes and Google Play, and we’ve got a regular RSS feed too!

Notes

-

-

- Introduction to Truth Tables.

- Philosophy Bro.

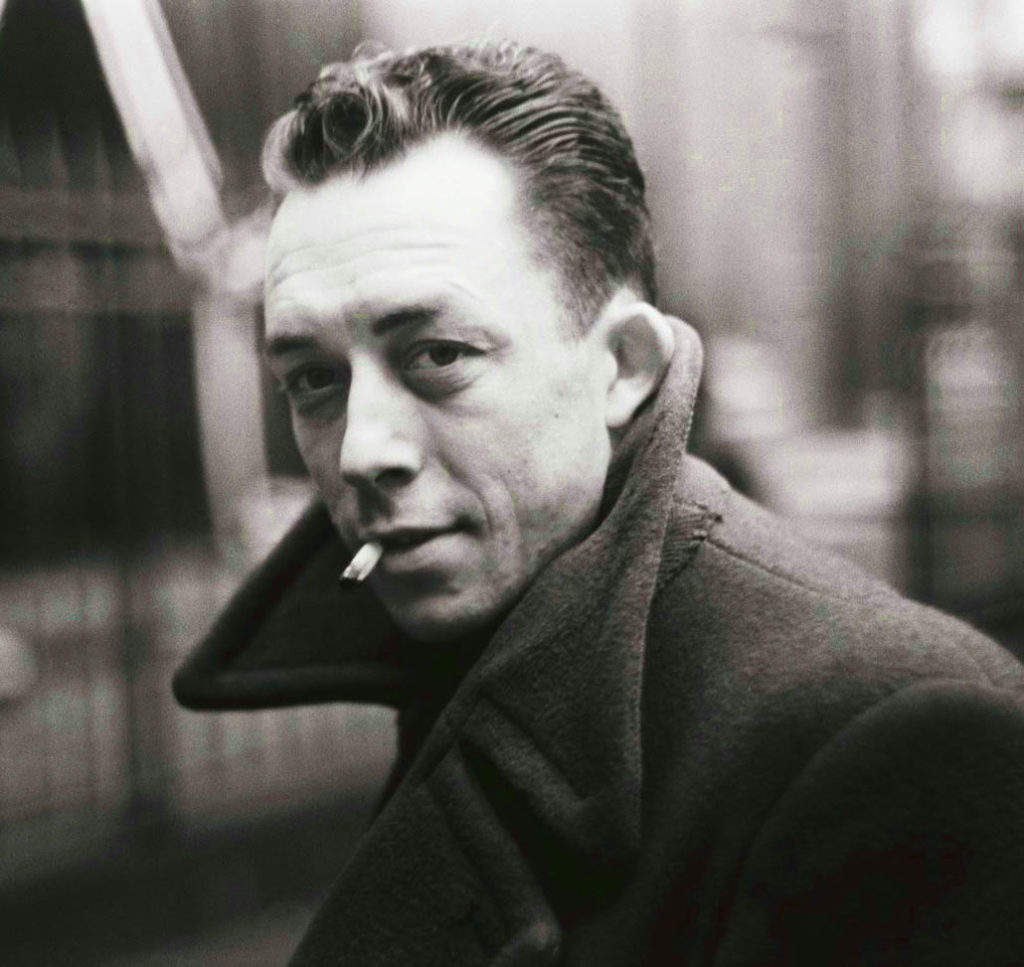

- Albert Camus, Nobel Prize winner.

- Cole’s essay on Facebook that attracted over 18,000 engagements.

- WebMD on tubal ligation.

-

In case you were wondering, yes, Cole’s photo above is a tribute to Louise from Bob’s Burgers.

-

You Tell Me!

For our future “You Tell Me!” segments, Cole proposed the following question in this episode, for which we invite your feedback: When you’re writing or making an argument, the question always to ask yourself is why it matters. It’s the “So what?” question.

Let us know what you think matters! Twitter, Facebook, Email, or by commenting here below.

Transcript

Transcribed by Drake Boling, September 20, 2017.

For those interested, here’s how to cite this transcript or episode for academic or professional purposes (for pagination, see the printable, Adobe PDF version of the transcript):

Weber, Eric Thomas, Anthony Cashio, and Cole Nasrallah, “Quality Philosophy for Everyone,” Philosophy Bakes Bread, Episode 36, Transcribed by Drake Boling, WRFL Lexington 88.1 FM, Lexington, KY, August 1, 2017.

[Intro music]

Announcer: This podcast is brought to you by WRFL: Radio Free Lexington. Find us online at wrfl.fm. Catch us on your FM radio while you’re in central Kentucky at 88.1 FM, all the way to the left. Thank you for listening, and please be sure to subscribe.

[Theme music]

Weber: Hey everyone. This is WRFL Lexington, 88.1 FM, all the way to the left on your radio dial. This is Eric Weber and we have got a great episode for you today with Cole Nasrallah. This is episode 36, believe it or not, but it’s hard to believe that we have had this many at this point, of Philosophy Bakes Bread. This is a really fun episode with someone that Anthony and I met at a conference in Asheville, North Carolina, at UNC Asheville. It was a ton of fun. I hope you enjoy. Do send us your comments, thoughts and so forth. We love hearing from you.

[Theme Music]

Cashio: Hello and welcome to Philosophy Bakes Bread, food for thought about life and leadership…

Weber: A production of the Society of Philosophers in America, AKA SOPHIA. I’m Dr. Eric Thomas Weber.

Cashio: And I’m Dr. Anthony Cashio. A famous phrase says that philosophy bakes no bread, that it’s not practical. We in SOPHIA and on this show aim to correct that misperception.

Weber: Philosophy Bakes Bread airs on WRFL Lexington 88.1 FM, and is distributed as a podcast next. Listeners can find us online at philosophybakesbread.com We hope you’ll reach out to us on Twitter @PhilosophyBB, on Facebook at Philosophy Bakes Bread, or by email at philosophybakesbread@gmail.com

Cashio: Last but not least, you can call us and leave a short, recorded message with a question, or a comment, or, as always, bountiful praise. Pile it on. We may be able to play on the show. You can reach us at 859-257-1849. That’s 859-257-1849. On today’s show we are very fortunate to be joined by Cole Nasrallah. Cole is an author and a teacher at a private girls’ academy at the College of Southern Nevada, near Las Vegas Nevada. She is also a dang good photographer. Cole is here with Eric and me at a conference on the Future of Philosophical Practice at UNC Asheville, in the lovely hills of the western part of North Carolina. We heard Cole give a killer paper earlier today, and we were just really excited to talk to her. We grabbed her immediately and said, “You have to come be on the show.”

Weber: Cole delivered an excellent paper on the elements of high-value philosophy and audience accessibility. We thoroughly enjoyed the paper and we had to get you on the show, and it was terrific. We are going to talk about those two things today. Before we get there, our first segment, Cole, we call “Know Thyself.” We want to know, first of all, do you know thyself? Tell us about yourself. We are going to, as the next step, talk about how you got into studying philosophy, as well as what philosophy means to you. Before we get there, let’s just hear about you. Tell us about yourself. Do you know thyself?

Nasrallah: When I was younger, I thought I was invincible, and I recently learned that I’m not. I was wrong about that.

Cashio: That’s always a bummer. So you know you are not invincible.

Nasrallah: I know I think I can know myself and then I find myself dramatically wrong. Then I think I know myself and I’m wrong again. I know what I’m not. I’m not invincible.

Cashio: Tell us a little about where you grew up, and how you ended up in Nevada. Were you always from Las Vegas?

Nasrallah: No. I grew up about four hours from where we are now, in what many people call ‘Deliverance’ country.

Weber: You grew up in Deliverance country, you say, in North Carolina?

Nasrallah: I did, in a fire district called Meat Camp.

Cashio: Wait. What’s a fire district?

Nasrallah: A fire district is too small to be a town or a city or anything else. It has a volunteer fire department, and those boundaries are what define the boundaries of the fire district.

Weber: So, it’s a big city, is what I’m hearing. (laughter).

Nasrallah: Massive. Bumpin’ at all hours.

Weber: How many people live in Meat Tower?

Nasrallah: (laughter) Meat Camp.

Cashio: Meat camp isn’t much better… (laughter)

Nasrallah: Meat tower sounds salacious. (Laughter). Sorry. I don’t know. I don’t know they were counting, or countable. It was extremely rural. I didn’t have electricity for the majority of my youth. For example, the house was heated with a kerosene heater. It was extremely rural.

Cashio: How did you go from Meat Camp to Las Vegas?

Nasrallah: I chased experiences and men a lot, and life, and adventures. One thing I’ve known about myself since I was very small was that if I went anywhere in life, it would be my intellect that took me there. I moved from several different college programs and several different careers, trying to find myself, having only the luxury of getting myself into terrible situations and figuring my way out of them and loving it. I have lived all over, and it was a slow migration process.

Cashio: So you haven’t always been a philosophy teacher. What are some of the other careers you have had?

Nasrallah: I was a commercial photographer. I did that to pay my bills while I was in school, in various different, schools, especially when I didn’t get grants or funding otherwise. That’s pretty much it, commercial photography. I also wrote and published some stuff. As is the case with a weird number of philosophers, I did computer programming.

Weber: Interesting. Cole, you said that you had a sense that what was going to lead to your future was something intellectually. I suppose you mean instead of your excellent tennis skills, or… you didn’t think computer science would do that? Why not computer science?

Nasrallah: It wasn’t specifically philosophy. I feel like if you’re excited about problems and your ability to problem-solve, you are more receptive to adventures and unknown situations, and possibly dangerous situations. Jumping into the unknown is not intimidating when you have that kind of confidence in yourself.

Weber: So, the intellectual aspect that you felt really comfortable with, and you didn’t see as much in others? Is that what you mean? This courage to jump into things?

Nasrallah: I trusted that there were no problems that I could get myself into that I couldn’t get myself out of.

Cashio: You thought you were invincible?

Nasrallah: I thought I was invincible!

Weber: That brings us full circle. This brings us, then to the question of how you got into studying philosophy.

Nasrallah: I went back to school to study secondary education. I wanted to be a high school teacher. I took a philosophy class and it was like coming home. I had never done it before. I was like, “This is what I have been doing all along. This is me.” I immediately changed my major with the intention of teaching after this. You don’t have to have a degree in X field to teach X. I knew I wanted to study philosophy, and if I got my way, I would be teaching philosophy, preferably to younger students. High-school age, not necessarily college.

Cashio: That’s a special kind of challenge that we’ll talk about in the next segment. What was it you said, philosophy was like coming home? What about it was so…

Nasrallah: I had taken a couple classes at that point, and I didn’t particularly enjoy them. I enjoyed learning, but the way people approached problems or questions or puzzles, or even the way people delivered information was just boring to me. It was uninteresting and not argumentative. It didn’t have that argumentative posture to it, that questioning, challenging posture. Not to mention the analytic aspect, where you approach something from several different directions and try to falsify it, the idea that I didn’t need to prove something was true so much as I needed to prove something false. I really enjoyed that. When I saw truth tables for the first time, I was like, “There’s a shorter way to do this. I know there is.” If you can disprove it, you don’t need to go through the whole process.

Cashio: For our listeners who haven’t had the luxury of taking a logic class, can you tell us what a truth table is?

Nasrallah: A truth table takes a proposition and runs every possible scenario with it to see if it will yield a true outcome.

Weber: A proposition, for anyone unacquainted, is a statement like, “Tom is a murderer.” Or, “If Jackie comes to the party, then Barbara won’t.” There are a number of different things that can happen. Maybe Jackie does come to the party. Maybe Barbara does come to the party. What do you say? Actually, then my statement is false in that case.

Cashio: All propositions can be either true or false. A truth table shows the combination of truth or falsity among propositions.

Nasrallah: That was natural to me for some reason.

Cashio: I think they are fun, myself.

Nasrallah: I love them. It was fantastic. Just the general skeptical nature of philosophy.

Weber: It seems to me that it relates to your interest in computers too. Truth tables, symbolic logic is fantastic for anybody who does computer programming.

Nasrallah: I think that’s why you see so many philosophers, especially philosophy of language, I think that turns into CS or computer science. That may be why I was a natural with it. I talk better to computers than I do people.

Cashio: You said so far that you were drawn to the analytic aspect of philosophy, this rigor. Maybe you could say: What is philosophy? What do you think it is, if you could give a short definition for our listeners, or for me and Eric.

Nasrallah: I don’t know if I can. My high school students ask me that sort of thing frequently, and I don’t particularly have an answer for them. Either I can tell them what it is we will be doing in class, which is we will be trying to find the right questions to ask to get at answers that are meaningful and successful.

Cashio: That’s pretty good.

Weber: Like the definition of philosophizing, doing philosophy.

Cashio: Looking for the right questions and thinking about what might be the right answers to those questions.

Weber: Is it any kind of question? Which kind of questions? Is “How many socks are in my hamper?” Is that a philosophical question?

Nasrallah: Are you going to get a meaningful answer out of it?

Weber: Yeah. Like 4. Is that meaningful?

Cashio: If you are looking for socks, then Yes!

Nasrallah: If you need to do laundry, if you are trying to arrange your day and whether or not you are trying to wash things. If you are worried about your feet stinking and ethical implications that might come from that.

Cashio: I think what Eric is saying is that there seems to be a difference between the question “How many hampers are in my socks… Sock are in my hamper, not how many hampers are in my socks.

Weber: That would be a weird question. That is some really small hampers. (Laughter). Or some really big socks.

Cashio: Versus “What ethical obligations do I have to others regarding the smell of my feet. Those seem to be different orders.

Weber: I think we might lose some people on what the hell the point of philosophy is.

Nasrallah: That’s in the weeds, right? I think that could be an interesting question, but we would have to pull it apart to figure out if it’s the right question for what we’re trying to sort out.

Weber: In think your demonstration, when you say something about the obligation, thinking about how we smell around others, that’s a really subtle social norm. How I smell near other people is an interesting question. Do I have an obligation not to stink?

Nasrallah: That would be a really interesting philosophical question because now we are talking about obligations and your role in society, and whether or not obligations are even possible. That would be a question that I would spend ages on and get really excited about.

Weber: There you go. You told us you were going to help us make sure we were asking the right questions. I was asking about my hamper, and I think you have just taught me some philosophy.

Nasrallah: I hope so.

Cashio: Speaking of teaching philosophy, this is a really good question I love asking people who specialize in teaching philosophy. This question we like to ask for our listeners who haven’t had the privilege of having a philosophy class, especially your good philosophy class: What is a good philosophical text they would use to jump into philosophy? Maybe to read about for first-timers? What would you recommend as a good philosophy text?

Nasrallah: Something that is going to help them for a specific class, or just something broadly that you enjoy?

Cashio: Broadly that you enjoy.

Nasrallah: I really enjoy Philosophy Bros translation on Descartes Meditations. What he does is takes obscure texts or obscurely written texts, and translates them into colloquial ‘bro’ talk, or frat boy talk, and it’s hilarious.

Cashio: Is it like, “Yeah bro, mind body dualism?”

Nasrallah: Rather than saying ‘mind-body dualism’, he will unpack that in philosophical terms and non-philosophical terms. It’s line by line in this specific book I’m recommending. The first meditations starts out with this long, drawn-out “For many years I have made these assumptions..” and Philosophy Bro makes an analogy where his character mistook somebody for who he was not, and was like, “Wow, I’m making all these terrible assumptions and I got really drunk and I can’t trust reality…” and develops it from there.

Weber: That’s a nice example. Check out Philosophy Bro, everybody. You are listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread with Eric Weber, Anthony Cashio, and Cole Nasrallah. Thank you so much everybody for listening. We’ll be right back after a short break.

Cashio: Welcome back everybody to Philosophy Bakes Bread. This is Anthony Cashio and Eric Weber here talking with Cole Nasrallah: a philosopher, a writer, and a sometimes artist. Quite good art. We are at a conference in Asheville, North Carolina, the Future of Philosophy seminar, and our idea for this episode is to hear from you about your paper, Cole, about the elements of high-value philosophy in public or audience accessibility. If we can, let us approach that in two steps. First, let’s talk about: what is high value philosophy? In the next segment, we will come to the matter of accessibility, which, you are really good on that. Let’s jump in. What is high value philosophy? Can you explain that to our listeners? Can you imagine we are some of your high school students? At the girl’s school. I’m sure that will be easy for you to imagine, Eric.

Nasrallah: this is going to be difficult. Every field has a way of doing things, and a level of gatekeeping in doing it. People who have the keys to entry. Without ever saying so, you get the feeling that there is a way of doing things, and a way of not doing things in any aspe3cific academic field. You have to be professional about it. You have to write about these things that people are interested in. High value philosophy would be philosophy that is valued specifically by those people as being of a very high quality or of great importance.

Weber: Interesting. So how many citations do I need on my paper?

Nasrallah: Exactly. That sort of thing. What kind of citations and what kind of language do you want to use? What kind of language should you use specifically for a topic or to appeal to a specific question? What sorts of questions would you be asking? What sorts of subjects are interesting? They are very narrow in this field and they are not always things that the public can relate to in any way, but they are things that are highly valued by that small cabal of philosophers at the top. Those gatekeepers.

Cashio: Can you give us an example or two of some questions that the gatekeepers are keeping?

Nasrallah: They are so obscure and unknown that I don’t know if I can explain them in a way that would be accessible. I can give an overview of a language one. We are not sure whether the meaning in a word comes from the person saying it, your locality, what sorts of things are around you, or what your listener thinks of when they hear it.

Cashio: That’s good, but why do you think that is not going to be connecting with the average person? They don’t care where the meaning of their words comes from?

Nasrallah: They may well care for where the meaning of their words come from, or where the real value of their words is, but when we talk about it, we use a lot of jargon, and we speak to even more specific issues than that extremely broad one. It narrows down even further to a point where I struggle to read it.

Cashio: I once struggled to read a paper. The whole paper was on the letter “A,” in upper-case and lower-case. It was not fun.

Nasrallah: I had somebody ask me early in my career what “the” could be referent of, and I was flabbergasted. I certainly, on the spot, can’t have that conversation. I didn’t know what vocabulary to use. I didn’t know how to talk about it. It’s everything but colloquial. We don’t have a way to talk about these things conversationally. We don’t have a way to create this high value work, or this work that is valued highly, that can be accessed by anyone but experts in a specific branch of philosophy. We didn’t communicate to each other all that easily if we are talking across fields.

Weber: This is interesting. You are raising some important points. I want to draw an analogy for a second. It seems to me that when I take my child to the doctor, I want to make sure I have got a high value doctor. By which I don’t mean expensive, I mean I don’t it to be a quack. I don’t want it someone to be selling me snake oil. The credentialing and the gatekeeping are really important to me. I’m so glad we have that in medicine. We can know things about the medicines we are being recommended. We can choose between risks of this and that. Thank goodness for the credentialing that helps. Would you see a similar kind of credentialing in an area like philosophy or do you find it very different?

Nasrallah: I’m pretty pluralistic about this. Should we define pluralistic? I am OK with multiple answers.

Weber: In that case, is that different from the case of the doctor? Are you pluralistic about philosophy having lots of ways of being quality, or of anything, including medicine?

Nasrallah: I don’t feel comfortable speaking to the medicine right now.

Weber: This is great. But you do feel comfortable saying that philosophy should be approached pluralistically.

Nasrallah: your kid is not going to die because we approach philosophy pluralistically. That seems to be a really important distinction.

Weber: I wonder about that. I teach business ethics, and if students go out and just sort of dismiss what we talk about and think, “No, we’re going to make another car like the Ford Pinto” was made, kids did die because the Ford Pinto is so unsafe. It’s a lot farther away and longer-term kind of harms, but if we don’t educate our people, the philosophy can influence folk’s decision making, but it doesn’t do it in the immediate run, usually. In the classroom, let’s say, or what have you in ordinary conversation.

Nasrallah: When we can justify a barrier to entry, by the immediacy of the danger or the threat, I just said I was invincible, so maybe that’s people influencing… On top of that, I don’t think one precludes the other, whereas you are talking about access to information, or informed consent. I maybe should have said that I focused on bioethics within philosophy. That might be my hesitance there.

Cashio: Can you tell us what bioethics is?

Nasrallah: Medicine and our bodies and our physical existence, quite often has ethical implications of how we deal with that and treat it and talk about it and think about it. Even something as simple as access to controlled substances is a bioethical question.

Weber: Right on. I think this is very interesting. I think you are telling us something important about philosophy, which is that it may be, and we emphasize on this show about how philosophy bakes bread, and these kinds of difference-making that can happen. Also, it’s good to play with philosophy, to entertain an idea, is the language we use. No one is going to get hurt when we entertain whether or not we ought to legalize marijuana in this or that state. Just having the conversation, nobody is going to die from this, and yet you can imagine all kinds of conversations where someone could die pretty soon on the basis of the outcome of a conversation in medicine.

Cashio: That brings us back to the high value philosophy, but it seems to be gatekept away. We’re talking about the letter “A” or some sort of high level…That is important, and some good work is being done. Is there a problem with that, being cloistered away?

Nasrallah: The reason we are having this conference is because philosophy is kind of dying.

Cashio: In what way?

Nasrallah: Student enrollment is abysmal, and philosophy is no longer in the public. Camus is one of my favorite examples. He was a rebel and an author and a philosopher around the time of the Nazis, and he was on the cover of Vogue. That is very much in the public.

Weber: I don’t think you want to see me on the cover of Vogue.

Cashio: I want to be on the cover of Vogue.

Nasrallah: I would love to be on the cover of Vogue.

Weber: I would love to see either of you on the cover of Vogue. I’m not sure I’d want to see myself on the cover. But I love that idea.

Nasrallah: We are so diminished from that stature that we once held. It seems to be a problem. We are doing something wrong. If you are gatekeeping to the point where no one can get in, that seems problematic.

Weber: I gave you the case of medicine. Medicine is a situation in which there is serious gatekeeping, and it’s very hard to get in. In fact, I remember a case where I had to make a decision that had to do with the term heart failure. I thought, if your heart fails, how can you live? You’re going to be dead, if your heart doesn’t work. But actually, it turns out heart failure is something you can live with your whole life. I didn’t know, and I had a PHD. I was making a decision about heart failure, and I didn’t know that was something you could live with. I made the decision, it was fine, we didn’t have a problem. But we are lucky, first of all. Secondly, my point is there’s language which can be, even in that case, unintentionally a barrier. In some places and times we intend, we make barriers. Some people do, in this gatekeeping function. How do you see the gatekeeping function working? Where do you see gatekeeping in philosophy?

Nasrallah: There is two forms of gatekeeping packed into what you just spoke about. You couldn’t be a physician just on a whim, but your physician needed to have the ability to take the language he was taught, and the medical knowledge he had, and impart that to you and lift that barrier so you could make an informed decision. We don’t engage in that at all in philosophy.

Weber: That’s a really nice example.

Nasrallah: You walked right into it. It was really happy.

Weber: We try and set things up on the tee for a homerun on this show.

Nasrallah: You telling me you did that on purpose?

Weber: No…yes absolutely. Perfectly intentional.

Cashio: We need this high value philosophy because it creates good content, but there is this gatekeeping behind it. Is there a way to…

Nasrallah: That’s why I brought up pluralism.

Cashio: How does the pluralism fit in?

Nasrallah: There is no reason we can’t have this high value philosophy. Nothing about writing for a popular audience or working with high school students or any of the other things I do prohibits this high value philosophy from existing or being valuable. I think we also need to value public philosophy.

Weber: What you are saying is that we can take terms like heart failure and we can explain them better in philosophy?

Nasrallah: Not just that we can explain them better but that the act of doing so is valuable.

Cashio: Now we could say, to use heart failure, but to go back to the philosophy of language, and explain what that is in a popular way.

Nasrallah: That’s interesting to people and how they can engage with these questions. It’s not all about expanding the field on the bleeding edge, which is something I wrote a lot about. That’s all that that high value philosophy does. It doesn’t invite anyone to the conversation.

Weber: I remember all kinds of terminologies and semiotics, and I remember one word want, “interpretant”.

Cashio: What is semiotics?

Weber: Semiotics is the study of symbols.

Cashio: What is a symbol?

Weber: I think people know what symbols are. A stop sign is a symbol. It’s not what a symbol is, but it’s an example of one anyway. I’m being a little Aristotelian in my answer.

Cashio: Stop sign is not a sign? Or is it a symbol?

Weber: It’s both.

Nasrallah: Thank you for demonstrating.

Weber: And yet what Cole is saying is very clearly important and accessible when you think about, for instance, how you should interpret a particular work of art. You were talking about language, but the notion of: Is the meaning of the artwork in the artist’s intent? Is it in the artwork itself? Is it in the person who is looking at it or listening or interpreting? Those are things that can really matter when someone gets really offended by a piece of art.

Nasrallah: Absolutely, or when somebody thinks they can buy a piece of art, or steals a piece of art, or duplicates a piece of art. There is no reason this can’t be happening in the public as well as academia.

Weber: Right on. This is terrific. We have been talking with Cole Nasrallah about high value philosophy. After a short break, we are going to come back and talk about audience accessibility in philosophy. Thank you everybody for listening. This is Eric Weber and my co-host Anthony Cashio. You are listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread. We will be right back.

Cashio: Welcome back, everyone to Philosophy Bakes Bread. This is Anthony Cashio and Eric Weber and we are here today talking with Cole Nasrallah about her paper, “The Elements of High-Value Philosophy and Audience Accessibility.” We are in Asheville, North Carolina, at a conference on the future of philosophy. We are having a great time.

Weber: This is actually only our second interview that we have ever done in which we have been in the same room together.

Cashio: Well, there is that lost interview…

Weber: That wasn’t an interview. We were talking about smelling each other’s feet in the other segment, so maybe there is a reason.

Nasrallah: You are leaning in really close.

Cashio: Cole, you have been successful in your writings, rendering philosophy accessible, and you have also been teaching philosophy to high school students. It seems like both of these activities and successes point to the importance of public accessibility of ideas. In the last segment we talked about how high-value philosophy is good, but the way we have gotten there in philosophy is through a gatekeeping, professionally, and has seeded the ground, we could say.

Nasrallah: Yeah, steal a line from my paper.

Cashio: It’s a good line. If you didn’t say it, I was going to set you up. Seeded the ground. That’s Cole’s line. I’ll cite my sources. To the general public, can you say how that has played out, the giving up philosophy’s place in the public?

Nasrallah: We act surprised that students don’t enroll in philosophy, and that nobody is asking us questions that we worked so tirelessly to answer. We shouldn’t be surprised about that, because of that gatekeeping, and because of the kind of philosopher that we have deliberately, or at least seemingly deliberately, we crafted out of our standards for high value and out of our concepts of what real philosophy is, we only do work for each other. The public isn’t interested in a philosopher’s philosopher.

Weber: What do you mean by that?

Nasrallah: I mean a philosopher who only does work for other philosophers, who is only interested in capturing the things that other philosophers are interested in.

Weber: I know this because I have heard your paper already. But you give us the example of the comedian’s comedian.

Nasrallah: I use that metaphor of the comedian’s comedian, or the musician’s musician, or the poet’s poet.

Weber: Comedians love them, right?

Nasrallah: They do because they value the audience. In comedy, the thing that is prized is the impact on the audience and the audience’s ability to appreciate the joke, laugh at the joke, and be a part of it. So, a comedian’s comedian, one who appeals most to other comedians, also appeals most to their audience.

Weber: Can we have all comedian’s comedians?

Nasrallah: Successful comedians are going to be comedian’s comedians, because success is defined in terms of the audience, and value is defined in terms of the audience for comedy.

Weber: So, does the philosopher’s philosopher value the audience?

Nasrallah: It doesn’t seem like they do. It just seems like they value other philosophers.

Cashio: What can we do about that?

Nasrallah: We can take that leap from the comedians and the comedian’s comedians, and saying that they are doing something right. Their success is linked to their audience. The things that they value, that comedian’s comedian, most highly lauded and valuable comedian is one who appeals to his audience and who does work with that in mind.

Weber: You have reached out to some big audiences with your own writing. How do you engage in that? If there is gatekeepers and language that you have got to use, what do you do if you want to reach people?

Nasrallah: I just do it. Yolo.

Weber: Is that a technical term?

Nasrallah: Yolo is the poor man’s carpe diem. It stands for ‘you only live once’. I find it highly philosophic. I love that it is kind of self-proving. Yolo. Why? Because yolo. It’s the ultimate philosophy to me. Circular.

Weber: You do it, but you do it in a way. How do you do it?

Nasrallah: I consider my audience. I first ask if the thing I want to write about is going to be interesting to my audience, if they are going to want to engage with it, what tools I need to give them to engage with it, should they so desire. I try to give them an example of how philosophers do engage with it, in a way that is comprehensible to them. Step one is picking something that is interesting to write about. While what does lower-case “a” or upper case “A” is not valuable to us. We can take that and make that valuable, though, by relating it to something to something relevant in current affairs, which is my favorite thing to do.

Weber: You also engage in work that is narrative, that tells some of your story, don’t you? Tell us about that.

Nasrallah: My most famous piece, I guess you could call it, is something that I just published on my own Facebook, and I wrote it somewhat out of frustration, because I had written an academic bioethics piece that I felt was extremely meaningful, and that I had put a lot of work into. It was the most important thing I had written to date at that point, and six people had read it.

Weber: What was that piece? What was it about?

Nasrallah: It was about medical gatekeeping and body autonomy.

Weber: What’s autonomy?

Nasrallah: Body autonomy is our rights to our own bodies. That’s the best way I can put it.

Weber: Auto-nomos. Auto is self, nomos is rule-making. You make your rules for yourself, for your own body.

Nasrallah: There are areas where that falls apart within contemporary medicine. The example I gave earlier. I can’t just go out and take a bunch of morphine. Not that I want to, but if I wanted to, I could not. There is gatekeeping in place to keep us from doing that. Not through morphine, but this had come to impact my own life. When I saw that this paper that I did not relate back to myself at all, for fear of being accused of being biased by that cabal of philosophers…When I saw that that was failing, that it wasn’t making a difference in the world, certainly not the kind of difference I wanted to make. I took to social media and I wrote a sister piece that uses the exact same concepts and same arguments I used in my academic piece, but in narrative form. I wrote about how it had affected my life, and I explained what body autonomy was, and I explained what medical paternalism is, and I explained or argued, rather, very publicly, why these things are hugely damaging to us, and to me personally.

Cashio: Where can our listeners find this?

Nasrallah: On my Facebook page.

Weber: You used the word paternalism. What is paternalism?

Nasrallah: Paternalism, which I guess I did not explain well enough in my piece, has nothing to do with the patriarchy and all that. I want to put that out front. It’s when somebody acts as a parent. They make decisions for you on your behalf, sometimes against your will. It’s roundly been rejected by the medical community, but we see it in areas like infant circumcision, or controlled substances, or in my case specifically, I did not want children, and I sought a tubal ligation, which is permanent sterilization, and I was pushed out unceremoniously of many doctor’s offices, I was laughed at by physicians because of this…

Weber: Why?

Nasrallah: Because there is an unspoken, but agreed-upon idea in America and elsewhere, I have learned in my piece, comments, people interacting with me, that a woman cannot have a full life if she is never a mother.

Weber: I can tell you, when I looked at this piece on Cole’s Facebook page, I saw at least 18,000 engagements with that post. That’s pretty impressive.

Cashio: Have you read all those?

Nasrallah: I have read all of them, and I have responded to almost all of them.

Weber: That’s a full-time job.

Nasrallah: It is. Which is part of the reason I think we don’t have more philosophers doing this, because there is no financial reward or anything. What I really value about that piece is that other people came and shared their stories. Now, not only do we have my argument, but my vindication through thousands of men and women sharing their stories about their struggle to be sterilized, or to get access to medical services that they needed but were denied because of medical paternalism.

Weber: Seems to me that the method you took in being narrative, at least in retelling the point of your formal piece, as a story, connected exactly with why we want people to talk about knowing thyself. It tells a story. It connects a person. I’m not surprised at all that you have seen a lot of success, though I’m impressed by how much. That’s really terrific. I do want to ask about accessibility in connection between your writing and your teaching at the high school level, because you are talking to all kinds of people when you write publicly. In the high school, we are talking about something like 13-18.

Nasrallah: Usually 14-18.

Weber: Can you tell us about what accessibility means in that context? IS it a totally different kind of accessibility or are there similarities there?

Nasrallah: We have already talked a lot about the kind of language we use, and you guys’ endeavor to unpack that language for your audience. That’s probably the biggest similarity and the largest barrier to entry for a general audience. We use so much jargon, as philosophers. I don’t even know if jargon is jargon.

Weber: That’s an interesting question. Jargon means a technical term.

Nasrallah: I would say it is.

Weber: Jargon is a technical term that is hard to understand. It is supposed to be helpful for being shorthand for a longer phrase, so you say a smaller word, so you don’t have to repeat the many words.

Nasrallah: It’s laborious. It takes a lot of work to unpack jargon for an audience. But it’s work I’m really interested in doing, because I think it makes our pieces and our work more interesting and have a far greater impact.

Cashio: So, we can have high value accessible philosophy.

Weber: That’s terrific, folks. You have been listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread. We have been delighted to be talking with Cole Nasrallah. This is Eric Weber. My co-host is Anthony Cashio. We’ll be back. Yolo. We will be back with one more segment after a short break.

Cashio: Welcome back to Philosophy Bakes Bread. It is your privilege this afternoon to be listening to Anthony Cashio and Eric Weber talk with Cole Nasrallah. Now we have some final big-picture questions as well as some light-hearted thoughts. We’ll end with a pressing philosophical question for our listeners, as well as some info about how to get a hold of us.

Weber: Yeah, with your comments, questions, bountiful praise. Cole, in what you described, you talked about how philosophers, unlike comedians, aren’t attending to our audiences. Fundamentally, the question is: What is the problem?

Nasrallah: The problem is that when our students go out, or our would-be students or just the general public and interact with their concept of philosophy, it has nothing to do with the work we are doing. If they go into a bookstore, any mainstream bookstore, at least, anywhere in America, and go to the metaphysics section, which is what we would understand as being Whitehead, you won’t find anything like that there. You’ll find things on chakras and crystal healing and auras and all manner of nonsense that we really hate.

Cashio: Listeners should know that Cole has a purple aura. Eric is rocking a blue aura today.

Nasrallah: Why is it purple?

Cashio: I don’t know. I practice. I know how to see them.

Nasrallah: That’s the problem. There is no explaining it. It’s nonsense. Where did you get that from? You produced it from nowhere.

Cashio: I have the eyes to see it.

Nasrallah: Further nonsense. If people think that those charlatans are philosophers, that’s no one’s problem but our own, because we withdrew from the public and started pleasing each other. We all started being philosopher’s philosophers. That left this area on bookshelves and on popular media, for the word philosophy, to completely vanish into auras and crystal healing and all of that nonsense. I’m going to call it nonsense. I hope that’s alright.

Cashio: Most people either don’t know what philosophy is, or they associate it with crystal healing.

Nasrallah: And it’s our fault. Just own it. We stepped out on them.

Weber: Just for what it’s worth, I want to make sure our listeners know what metaphysics means as a word. That isn’t just a crystal ball kind of language. Metaphysics is actually a word we use in philosophy. It has just been used in the way to be a category for books about using pyramids to heal yourself and so forth.

Nasrallah: I don’t know why, either. Do you know why?

Cashio: Sounds fancy.

Weber: It does sound fancy. They don’t know what it means. So what is metaphysics?

Nasrallah: Oh, don’t ask me to explain metaphysics. One of you guys has to do that.

Weber: Alright. Anthony, you want to give it a go?

Cashio: Metaphysics is literally beyond the physics.

Weber: Metaphysics, my understanding is that it’s a word that comes from the fact that there were all of these weird questions about the nature of things, that people didn’t know how to categorize in Aristotle’s corpus. They put them together in this book, and it happened to land in the book after physics. So they called it ‘after’ physics—metaphysics. Doesn’t really tell you what it means, but metaphysics refers to the nature of things, such as, “What kind of thing is time?” or, “What kind of thing is humanity?” For instance, in a practical question of, “Are human beings creates that have fallen? Or can we change? Can we be rehabilitated in prisons? Are some people naturally evil and you can’t change them?” Those kind of questions are metaphysical questions, in the non-sham way, I hope.

Nasrallah: I have an example I give my students. It’s fairly simple, because metaphysics concerns itself with what things are composed of. Just like physics does. We have this fun example we use in philosophy very early on, which is the ship that departs from a location. It has crew members, and it’s made out of wood. It is a ship. It departs. It sails around the globe, but as it does so, every piece of it eventually needs replacing and every member departs at some dock and is replaced by someone else. By the time it returns to its point of origin, it has none of the original parts and none of the original crew members. Is it the same ship? It’s a fun question. It’s an interesting question. It’s a question about what things are composed of. We can apply that to our own bodies. Our cells change over every few years. Are you the same person you were when you were born? In what meaningful way is that you? You are not made of the same stuff. Answers that might seem immediately apparent are not, when you start looking at them metaphysically.

Cashio: What makes something something? I have students think about holes. What makes a hole a hole? Something that exists by not being.

Weber: Except when you drive your car over a hole, you all of a sudden know, very intimately, what a hole is.

Nasrallah: A hole is just an absence of things?

Cashio: It’s an absence of things, but it’s also dangerous.

Nasrallah: It’s a little like that metaphysics question, but these are real questions that we hope have real answers.

Weber: It can certainly matter. If someone was responsible for a hole, and it’s not a thing, you can say, ‘Hey, I’m not responsible for anything’.

Nasrallah: I want to spell out hole like HOLE not WHOLE, because metaphysics asks about both.

Cashio: Are holes part of the whole or… (Laughter).

Weber: Imagine a whole section of the bookstore about this, about holes.

Cashio: Maybe crystals aren’t far off… the wholeness of the holes. We don’t want crystals and we don’t want aura readings,

Weber: Or pyramid healing?

Cashio: Well, we do want that. I guess my last question is– It’s kind of practical. Do you have any advice for our listeners if you are out there and you are like, “I want to get into philosophy, but my metaphysics section has Being and Nothingness, but it also has something on horoscopes, how do I determine good philosophy from bad philosophy if I have never taken a philosophy class at all? How do I avoid the snake oil salesman and the charlatans.

Nasrallah: As philosophers, the first thing we teach is how to deal with that problem. We teach critical thinking. We teach to ask questions. Its always been immediately apparent to me what is nonsense and what is not, but that’s because I have had that critical questioning posture even before I took a philosophy class. That may be why it felt like coming home to me. When you pick up a text and it is asserting things about reality, and not doing the hard work of trying to persuade you that those things are true, it’s not justifying what it is telling you in reality or something that resonates with you in a meaningful way, that seems to me to be the quackery, if you will.

Cashio: I always liked that word. I always just imagine a duck.

Weber: It has a good, ‘slap-in-the-face’: “You quack”.

Nasrallah: Good sound at the beginning: quack.

Cashio: One of our final questions comes from the inspiration for our show. We’re going to hit you with it. Are you ready? Would you, Cole, say that philosophy bakes no bread, as the famous saying goes? Or that it does? Why? How? Explain. Show your work. You have kind of already answered it, but what do you think?

Nasrallah: I think it has to be practical. I think the problem is that we are treating it like it is not practical. Of course I think it’s practical. I have used it to make my life better.

Weber: Tell us about that for a second.

Nasrallah: In writing that piece we spoke about earlier, for the public, I found other people like myself. That was hugely empowering. I was able to start a conversation that may change the way that we do medicine in this country. It’s not just going to be me, it’s going to be everyone else who joined in that conversation with me. It points to something and says, “Hey, it’s a problem. Let’s do something about it.” If philosophy is doing that, then it’s obviously baking bread.

Weber: Nice. Well, Cole, as you know, we want to make sure people know philosophy is serious as well as that there is a lighter side. We have a segment that we call ‘philosophunnies’.

Weber: Say ‘philosophunnies’

Sam: Philosophunnies!

(laughter)

Weber: Say ‘philosophunnies’

Sam: Philosophunnies!

(child’s laughter)

Weber: We would love to hear your funniest joke, funniest fact, or just a story about philosophy. Do you have something that you can think of that is funny or silly, or a joke about philosophy?

Nasrallah: I have a story that is kind of notorious about Wittgenstein. His friend Joan was in the hospital. She had just had her tonsils removed. He called her up and asked her how she felt. She said, “I feel just like a dog that had been run over.” Wittgenstein said, “No you don’t.” (Laughter). I don’t know if that needs explanation or not.

Cashio: Let it hang. Wanna do some of the jokes we have scrounged up here?

Weber: We have a couple philosophy jokes.

Nasrallah: I’m glad you liked it.

Weber: I don’t know if people will follow it. But it’s funny.

Cashio: We were talking about professionalism earlier. This might be a useful one when thinking about professionalism. If you can’t be kind, at least have the decency to be vague.

Weber: I passed my ethics exam. Of course, I cheated. (Laughter).

Cashio: That hits a little close to home. I’ve never cheated on an ethics exam. Let’s be clear about that.

Weber: I didn’t cheat on an ethics exam. I did tell my students that there is a special place in hell for people who cheat on ethics exams, and they thought that was really funny.

Cashio: My colleague and I dissolved our friendship over religious differences. He thinks he’s God. I don’t. That’s the story of me and Eric.

[rimshot, applause]

Cashio: Last but not least, we want to take advantage of the fact that we have powerful social media that does allow two-way communications for programs like radio shows. We want to invite our listeners to send us their thoughts about big questions that we raise on the show.

Weber: Given that, Cole, we would love to hear your thoughts, if you have a question you propose we ask our listeners for our segment that we call “You Tell Me!” We could hold, for example, a breadcrumb episode where we want to know what you think. Do you have a question that you propose we ask our listeners?

Nasrallah: The question I ask all my students whenever they write a paper, or even a short story or anything like that, or try to persuade anyone of anything, which is: Why does this matter? Why care? You should always be answering that to yourself, as well as to your audience.

Weber: The question is: So what? So what guys?

Cashio: Thank you, everyone, for listening to this episode of Philosophy Bakes Bread. Your hosts Dr. Anthony Cashio and Dr. Eric Weber, have been very lucky to be joined by Cole Nasrallah. We hope listeners will join us again. Consider sending us your thoughts on anything that you’ve heard today that you would like to hear about in the future, and about the specific questions we raised for you. So what?

Weber: Once again, you can reach us in a number of ways. We’re on twitter @PhilosophyBB, which, I believe, stands for Philosophy Bakes Bread. We’re also on Facebook at Philosophy Bakes Bread, and check out SOPHIA’s Facebook page while you’re there, at Philosophers in America.

Cashio: You can of course, email us at philosophybakesbread@gmail.com, and you can also call us and leave a short, recorded message with a question or a comment that we may be able to play on the show. You can reach us at 859-257-1849. Join us again next time on Philosophy Bakes Bread: food for thought about life and leadership.

[Outro music]