The Society of Philosophers in America (SOPHIA) is an educational nonprofit membership and chapter organization dedicated to building communities of philosophical conversation. We are made up of people from within and beyond the academy, people who are interested in deep, meaningful dialogue, and who aim to enrich public discourse, civility, and community.

As an organization, SOPHIA was incorporated in 1983 and has recently undergone some strategic planning and restructuring. In that process, we drafted a mission statement, posted here below, guided by an understanding of who we are, what we value, and where we are going.

Strategic Plan

Strategic Plan

The leadership of SOPHIA engaged in strategic planning in the spring of 2015. The result was a document that you can read as a Web page here or as a printable Adobe PDF file

For the full statement in our plan about who we are, what we believe, and where we are going as an organization, see our plan.

Mission Statement

The mission of the Society of Philosophers in America (SOPHIA) is to use the tools of philosophical inquiry to improve people’s lives and enrich the profession of philosophy through conversation and community building.

Core values

A) Building philosophical community and engagement – Philosophy is for everyone.

B) Philosophical inclusiveness – Philosophers learn from others.

C) Respectful communication – Everyone has a voice.

D) Professional excellence and public relevance – Philosophy goes beyond the realm of academia.

For a more detailed statement of our values, see our full strategic plan.

Goals and Objectives

Goal 1: To create publicly-engaged SOPHIA chapters that are locally-focused

Goal 2: To build a collection of thematic materials and meeting guidelines

Goal 3: To use technology effectively

Goal 4: To engage with the profession on public philosophy and digital humanities

For a more detailed statement of our objectives, see our full strategic plan.

History

The SOPHIA of today is a reconstruction of the organization that was founded on November 15, 1983. SOPHIA is a nonprofit organization incorporated in the state of Connecticut. In its early days there were a number of different but related aims and values that motivated the group. One factor had to do with frustrations with the ways in which philosophy was practiced in institutions of higher education in America. The other motive concerned the need for philosophy to attend to matters important for people’s lives. The first motive was inwardly focused on academia. The other had more to do with the public value of philosophy and the need both for scholars to share that value with people beyond colleagues in philosophy departments or higher education in general, and for the issues and voices in public life to inform and inspire scholarship.

From the earliest days, a few philosophers were key inspirations for the group. Among them was the late John Smith of Yale University (Obituary in the New York Times). Smith enlisted the help of Jack Loughney, who served as the society’s second Executive Director and later as treasurer and trustee for decades. Loughney kept the society together through many changes that arose as a result of the two distinct aims for its founding. Bruce Wilshire of Rutgers University was also a motivating force in the group, especially for the cause of advancing pluralism and open-mindedness in the American Philosophical Association.

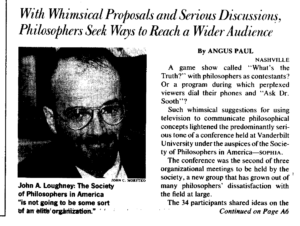

In the period leading up to SOPHIA’s founding, philosophical meetings were not typically discussions. Instead, they revolved around narrowly focused and highly abstract paper presentations. Audience members were generally aggressive in their responses, aiming to undercut the presenter’s argument. Today, philosophical meetings are often vastly more constructive and welcoming than they had been. At the time, it was a radical idea to get a group of philosophers together without a keynote speaker, without paper presentations, nor a particular road-map of where the conversation was to go. Smith, Loughney, Wilshire, along with Professors John Lachs of Vanderbilt University and John McDermott of Texas A&M University, and many others involved in the “pluralist movement,” were among the leaders of a coalition concerned about the distance philosophy had traveled away from accessible and inviting conversation about values and the intellectual challenges that matter to the public.

In defiance of then-narrowminded analytic philosophers, SOPHIA’s first meeting was held at Harvard University. Lachs, today the Chairmain of SOPHIA’s Board Trustees, explains that “The success of [SOPHIA’s conversational] approach surprised us and enriched our philosophical work.” Members of the group believed in the potential for philosophy to be relevant again, to be inviting and open-minded, even open-ended. This shift in tone and approach was vital to the future of the organization.

It is worth nothing that SOPHIA has long recognized and welcomed many open-minded and publicly relevant SOPHIA-friendly philosophers, including those who think of themselves as part of the “analytic” tradition. Much has changed since the 1980’s in that regard, yet such changes are what early members of SOPHIA were calling for in the profession.

Concerned with the profession of philosophy, early leaders of SOPHIA worked to steer the APA towards more philosophical inclusiveness. There are far more women in philosophy today, for example, though there are still a number of groups very poorly represented in professional philosophy. From its earliest days, SOPHIA included women among its leaders, beginning with Sandra Rosenthal, Beth Singer, Thelma Lavine, Mary Clark, Evelyn Shirk, and later Nancy Simco, Jackie Kegley, and others. While changes to the profession are still needed, the people who fought for greater pluralism saw a number of movements for positive change in the APA.

In 1988, The Chronicle of Higher Education featured a piece on SOPHIA that demonstrates clearly the two threads motivating the group. The article, “With Whimsical Proposals and Serious Discussions, Philosophers Seek Ways to Reach a Wider Audience,” highlights a period when SOPHIA organized a number of conferences, bringing philosophers together to talk about the future of the profession. Some voices advocated for reaching out beyond the academy as a key value to advance, while others cared primarily about pluralism, and little about bringing philosophy out of the ivory tower.

As a result of tension between different aspects of the motivations for SOPHIA, and the retirement of many of SOPHIA’s early leaders, the organization’s mission and charter needed refocusing. After many years, the leadership invited new and younger members and officers in 2008 with the intention of focusing on the value of engaging the public philosophically about matters of importance for everyday life. From 2008 to 2015, SOPHIA put on over a dozen local symposia and practical or socially-relevant professional panels, including:

- “

The Nature and Challenges of Community,” The University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS, 2015

- “If Steinbeck Was a Farmer,” Kegley Institute for Ethics at California State University at Bakersfield, 2014

- “Should Everyone Go to College?” University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS, 2013

- “The Value of a College Degree and of a Philosophy Major,” Eastern APA panel, 2013

- “Philosophy’s Guidance for Civility,” Eastern APA panel, 2012

- SOPHIA session at “The Moral Brain” conference hosted at New York University, New York, NY, 2012

- “Food Symposium,” Pacific Lutheran University, Tacoma, WA, 2012

“Defending Philosophy in the Academy,” Eastern APA panel, 2011

- “Neuroscience and Pragmatism,” Potomac Institute, Washington, D.C., 2011

- “Disability, Civic Responsibility, and Community Friendship,” University of Mississippi, Oxford, 2011

- “SOPHIA Symposium on the work of Anita Silvers,” Eastern APA panel, 2010

- “Ethics at the End of Life,” University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS, 2009

- “Midsouth Environmental Symposium,” Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, Carbondale, IL, 2009

- “Responding Ethically to Climate Change in the Willamette Valley,” University of Oregon, 2009

In organizing these events, SOPHIA sought and was awarded nine grants from the American Philosophical Association and the Mississippi Humanities Council, as well as substantial institutional support from the University of Mississippi, California State University Bakersfield, Southern Illinois University, the University of Oregon, and Northern Arizona University, to name only recent contributing institutions. Past supporters include Harvard University’s School of Education, Pennsylvania State University, Yale University, Vanderbilt University, Emory University, Westfield State University (Massachusetts), the University of New Mexico, and the Cabot-Hocking Trust.

The guiding values behind these gatherings included 1) an appreciation for the public value of philosophy, 2) the felt need for philosophy to be engaged not only within the academy, but also in conversation with people from other fields and from beyond higher education settings, 3) the recognition that people beyond the academy can contribute invaluable insights for scholars – that philosophy and wisdom are a two way street in philosophical conversations. SOPHIA leaders continued to organize traditional academic panels at professional events as well, but only ones focused on matters of public value. The greater innovation, however, was to open up forums for philosophical dialogue, not just reading papers to audiences.

Over the years, SOPHIA has demonstrated and felt the value of conversational meetings, which can be productive and rewarding. We also have found that they generally do best when conversations begin with a very short document as a prompt, such as just one page or two, which participants can read at the event before starting the discussion. That way, all are literally on the same page, and it is easy for all to jump in to the discussion about philosophical matters raised in the piece. SOPHIA events are not limited to that format, but philosophical discussions after films are a great example of the kind of experience that one can organize.

SOPHIA has also transitioned from being an honorary society to a membership organization. The aim of community-building made clear that we needed to establish local chapters of SOPHIA. Thus, today, SOPHIA’s aim is to build communities of philosophical conversation, understood broadly to include local, national, and international communities, with in-person and online forums. The qualification that SOPHIA is “in America” was never intended to limit philosophical engagement across boarders. It remains in our name as a matter primarily of our organizational, historical origin. One of our members is establishing a chapter in India, and we hope more and more people will establish chapters around the world.

Another hope for SOPHIA is that the many people over the last few years who have been asking how they can get involved and advance these shared values and goals do join us, both online – nationally – and locally, in chapters around the world. Reading the news today, it is clearer than ever that there is a need for richer, more philosophical dialogue in the public sphere. SOPHIA’s aim is to open up and support forums in which more of that kind of philosophical and conversational community-building can take place and flourish.