| By Raymond D. Boisvert |

One of my nieces helps publicize Maine cheesemakers. She invited my wife and me to an actual “cheesery.” Yes, it’s a cheesy name but one that says it all. Why bother with fancy, disguised labels like “creamery” or “dairy farm” when what you do is make cheese. The setting is lovely: The Belgrade Lakes region. The address is Pond Road and, sure enough, the land rolls down to a body of water. Strangely enough, its official name is Messalonskee Lake, not pond but, as we know, a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.

The cheesery is small, homey, artisanal. Milk comes from the farm’s own 60 or so goats. There are also sheep. Where there are sheep and goats, this is what a city dweller notices, there’s also a certain aroma, and bugs. Plenty of bugs. Bugs are central to the philosophical lesson to come, but that’s for later. A great number of the bugs are visible, hovering around the animals (and the human visitors). Others are invisible, in the soil, in the guts of the animals and the humans. Some bugs, though, come in neat packets and are carefully stocked. These have actually been sought after and, yes, paid good money for, by the cheesemaker.

Bugs are annoying. We try to avoid them. Bacteria are annoying and disease-causing. We try to avoid them as well. In other words, for quite a while now, we have been “Pasteurians.” We have succeeded, in the tradition taught us by the great Louis Pasteur, in eliminating unwanted, disease-causing bacteria from our foodstuffs and ourselves. The background scenario was fairly straightforward: bacteria = bad = must get rid of them. But now we are confronted with cheese makers who spend good money to acquire and then use bacteria. What is going on?

Well, several things about which a history of ideas can enlighten us. The general topics have familiar and very old labels: the one and the many, the pure and the impure. These labels can be matched with a historical one: the ancients and the moderns.

Interestingly enough, the ancients, it turns out, tended to embrace multiplicity and mixture. We often don’t notice because we read their texts through the interpretive lenses of later thought. Philosophers, influenced by Modernity, will tend to talk about the “good,” for example as if it were a singular thing.

This can be a source of problems when life is a complicated adventure. The ancients like Plato and Aristotle did pretty well. One of the famous maxims inscribed at the temple at Delphi read “Nothing in Excess.” In line with this saying, philosophers recognized the need for some balance among multiple elements as defining the “good.” Plato thought in terms of an optimal society, one in which “good” was to be defined by the proper arrangement of the multiple and differentiated humans who made it up. Aristotle invented a word, “eudaimonia,” to indicate “happiness,” or human “flourishing.” A flourishing life involved multiple elements: proper organization of dispositions, good habits, friends, some luck as regards things like health and a stable society, all accompanied by a general reasonableness and attention to what is learned from experience. Eudaimonia was always a complex affair.

Then, came a shift. After Aristotle, Epicurus defined “pleasure” as the content of happiness and thus goodness. As a philosopher, he asked a complicating question: what is pleasure? It turned out to mean “ataraxia,” non-disturbedness. A life lived in equilibrium, with minimal disturbances, would be the most pleasant life. The Stoics, often contrasted with the Epicureans, had a similar ideal, “apatheia,” absence of powerful emotional upheavals.

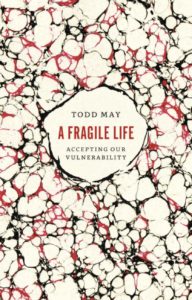

These post-Aristotelian moves marked a major change: an inward turn. Things to be avoided, e.g. disturbances, emotional upheavals, upsets to a life lived in equilibrium–all of these arose from what was outside us. The less we involved ourselves, the less we made ourselves vulnerable, the greater were the chances of achieving a pleasurable, minimally disturbed life. The older ethics assumed that a good/happy life was not possible unless there were people on whom we could depend. The newer one followed the trajectory sung by Whitney Houston: “And so I learned to depend on me.”

Religion added another ingredient. This arrived via the teachings of a Persian sage called Mani. The internal/external distinction became a sharp good/evil split. Manichaeism described a world in which good and evil, light and darkness, spirit and matter were irreconcilable. Each could be easily identified. Matter was evil, spirit was good. Within this context it made perfect sense for large numbers of men, aspiring to a good life, to withdraw from the world and become cloistered monks. Also encouraged was a tendency as old as humanity: identifying scapegoats. Women labelled as witches felt this wrath, as did heretics. Later writers traced political problems to “parasites,” either the idle rich (Lenin lambasted them), or poor folks (Ayn Rand lambasted them). The Nazis treated their enemies as parasites and germs, agents in need of eradication.

Newspaper headlines about the notorious E. coli do not help, especially when they fail to mention that most strains are harmless and even beneficial. Eliminating them would be disastrous for our health. Better to work with them. This is where cheese making offers an object lesson. Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus casei – don’t eliminate them. Welcome them, cooperate with them. The results: healthy, tasty cheeses.

Pasteurizing plant, from the McCord Museum.

The post-Aristotelian dispensation in ethics led readily to a fetish with eliminative purification. Cheese making returns us to a more complex, i.e. more concretely accurate, setting. It’s not one that is anti-Pasteurian. Its more accurate label is “post-Pasteurian.” The philosophical framework that accompanied the “eradicate to purify” move, the post-Aristotelian inward turn, was doubly problematic. (1) A good life was to be achieved by insulating ourselves from the vagaries of existence. (2) The dispensation encouraged a combat mode. It fostered, in other words, not just withdrawal, but attempts at purification through eradication of what was considered, unilaterally and unequivocally, evil.