| By Paul Croce |

Can academics support the democratic struggle not just to critique fake news, but also to engage the public in the stories that make those false facts appealing?

Intellectual responses surely help identify the really true stories, but the problem of fakery runs deeper because of the way fake stories can seem plausible, at least to segments of the population, as a way to explain what’s happening around them. The political problem with “post-truth” is that, in its tendencies toward exaggerations of the truth, it reinforces already sharp suspicions about contrasting points of view. And it gets worse: people convinced by the fake stories, especially ones with lurid depictions of contrasting positions, tend to believe that the other side should not even get a hearing. At the righteous extreme of these extreme reports, fake news encourages the assumption that one side will simply need to defeat the other.

-

Making a Case for Listening to the Stories that Make Fake News Appealing

Post-truth statements are not hidden in dark corners gaining no attention. The kindred label, “Alt.Truth,” is in wide enough circulation to be the name of a popular Homeland episode. The wide appeal of these distortions, not their merits, makes them an issue. And it is our democratic culture and commitments that makes popular appeal significant. Respect for the voice of the people calls for attempting to understand how stories stripped of truth gain support. That suggests a special role for academics and teachers, as long as they do not get so caught up in their learned ways that they come to believe that they can’t learn anything from the thinking of the average citizen. One of our most intellectual of presidents, Thomas Jefferson, even believed that the tangible experiences of “a ploughman” would foster a better decision on “a moral case” than the abstract reasoning of “a professor.” Even when not learned, citizens can shed light on the lived experience of democracy, and those lessons travel on the wings of stories instead of the highways of scholarship.

In The Death of Expertise, professor of comparative politics Thomas Nichols honors the “specialization and expertise” that have produced the marvels of the modern world, and he laments the squandering of those achievements by the “unfounded arrogance” of citizens with “stubborn ignorance.” Philosopher Zach Biondi has issued a call to action for philosophers to help the public “recognize incompetence and poor argument.” Investigative journalists gamely try to bridge the gap between knowledgeable professionals and citizen indifference about expert insights. The organization Snopes evaluates public statements from True to Mostly False to downright Legends that circulate despite their lack of factual support. These experts do great work and deserve wide support. This approach shows great faith in the power of knowledge, with the tacit assumption that people just need to learn objective facts to correct the appeal of false facts.

Accuracy of facts is surely important, and they can sometimes be persuasive, but the appeal of misinformation persists. American psychologist William James offers helpful insights for addressing this challenge. He formed his thoughts in the late nineteenth century, just as the age of information abundance and expertise was taking on its modern shape. His psychology both helps to explain the appeal of false facts and suggests ways to respond to them. Without understanding the appeal of fakery, the responses won’t get very far. His insights can actually support the goals of the experts and fact checkers.

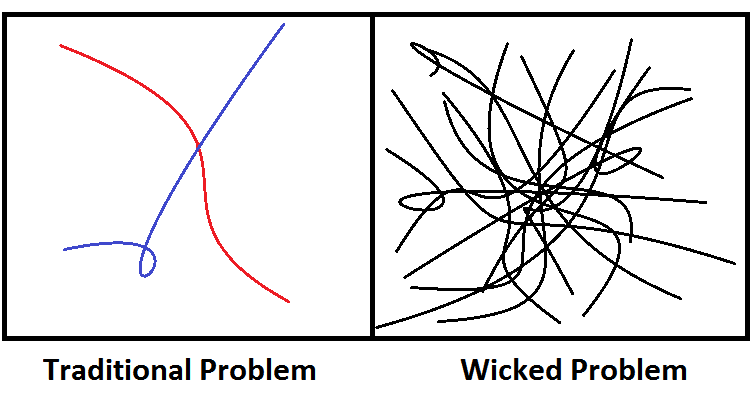

First, James points to the formative role of selective attention in the establishment of sharply different views. In the vastness of experience, there is not only room for different interpretations of facts, but also for selection of different facts. To make sense of situations, James observes, we select portions of the abundant facts to construct likely stories, which provide guidance within the complexities of experience based on prior assumptions. The most basic elements of false information can generally be corrected rather directly with true information. But the false is often not simple; more complex settings call for deeper inquiry into the sources of those likely stories.

Second, when facing the resulting cacophony of different points of view, James acknowledges the complexity, and suggests the humbling effect that awareness of this range of interpretations can have for coping with this diversity. In reminding that “to no one type … whatsoever is the total fullness of truth … revealed,” his point is not that there is no truth, but that truth is immense and complicated. Even with his awareness of human limitations in the face of the vastness of experience, he firmly critiques those ready to use the elusiveness of truth as a cover for active promotion of untruths. In recognizing the rich complexity of truth, he points to the need for constant inquiry and cooperation among us mere mortals who each have portions of truth in degrees. Attention to the truths of others can even shed light on one’s own truths.

James’s insights about selective attention and the overarching complexity of experience suggest the importance of looking at problems of fabricated news not just as reported (false) information, but also as storytelling, people’s efforts to find meaningful truth in their experiences. Every claim to fact is embedded in a story, which enables that fact to be accepted or not based on the plausibility of the story surrounding it. Awareness of the power of stories is not an endorsement of the sometimes false facts within them, but an acknowledgement of their significance in the human mind, and this awareness can also serve as a resource for addressing their unsavory power. This is especially important when the well-informed voices of experts are not enough to persuade citizens. And this is most especially important in a democracy that values the voice of the people.