| By Preston Stovall |

Part 1: Speaking to the Middle

I

An educated populace is crucial for a well-functioning democracy, and in the U.S. the use of pamphlets, periodicals, opinion pieces, and public letters, stretching back before the revolution, testifies to the importance that Americans place on an educated public. The use of these devices has helped keep American citizens apprised of the problems we face, and in the early Republic especially it was an important method of consensus-building.

This interest found kindred expression in a general concern with education in the United States and the colonies, one that many of the founders shared: Benjamin Franklin was instrumental in the creation of what would become the University of Pennsylvania, Benjamin Rush founded both Dickinson college and what would become Franklin and Marshall College (‘Franklin’ named after Benjamin), and Thomas Jefferson worked to establish a system of schools in Virginia, from the local level up to the University of Virginia, with the aim of selecting the brightest pupils for further instruction at each stage.

These projects were animated by a sense of education as something like a public resource for the American people. As a public resource education offers individual citizens not only a path to gainful employment but also the possibility of improving our lives by developing the habits of thought and conscience that accrue through a period of prolonged engagement with the thoughts and deeds of those who came before us. And by creating such citizens American education offers, for the public, successive cohorts able to sustain the intelligent collective reflection over the shape of American society that attends our participation in this experiment in self-government.

Thinking of education as a resource for the American people highlights the importance of the principles and institutions that shape its management. For just as the principles governing (e.g.) Fish, Wildlife, and Park services for U.S. citizens are enforced by various institutional mechanisms, and these geared toward the end (in part) of allowing us to enjoy the public goods that come with resource use in wilderness areas, so are the institutions of education meant to be run by principles that enable American citizens to enjoy the personal and social benefits that come with education. And just as access to wilderness areas redounds on the health of American society and its citizens, so does access to education. This analogy suggests that if education is a resource for the American people then educators—as stewards of the use of that resource—have a duty to mind the institutional norms and mechanisms that enable the public to enjoy its benefits, just as employees of FWP have a duty to mind resource management in wilderness areas.

Despite its close ties to the founding of the Republic, in practice higher education, as with political representation, would remain for generations the province of the elite, however. When Jefferson speaks of the “best geniuses” that will be “raked from the rubbish annually” by the school system he proposed for Virginia (Ford 2010, 61), his candidate geniuses were white men from families wealthy enough to pay for higher education.

It is a testament to the animating ideals of the American system of government that we have gradually overcome some of the barriers obstructing the universal enjoyment of our rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. If the development of American society is to proceed on the basis of a more thorough realization of the principles of individual liberty and collective self-government that animate our country, and if education in the United States offers both the individual benefit of personal betterment and the public good of intelligent control over the shape of our union, then it will be important that American educational institutions foster the mutual understanding that precedes collective action. For we cannot effectively work together on a common project if we do not understand what our partners want and are trying to accomplish.

II

Unfortunately, we live in a time of increasing political polarization in the United States, and this makes it harder for people to understand one another across political divides (see section III for the details). This polarization has grown sharply in the last twenty-five years. According to the Pew Research Center, in 2016 more than 50% of those identifying either as Democrat or Republican held not only an unfavorable but a very unfavorable view of the other party (Pew Research Center 2016b). By contrast, in 2014 43% of Republicans and 38% of Democrats had a very unfavorable view of the other party, and in 1994 these percentages were just 17% and 16%, respectively (Pew Research Center 2014). This growing divide is reflected in different views about what our top priorities should be (Jones 2019). There is also a rising sense that public discourse on political issues has become too divisive (Pew Research Center 2019).

This situation makes it difficult for people of different political views to talk to one another without the conversation devolving into acrimony. That in turn makes it difficult to share and improve on the ideas we have about what we are facing and what to do about it. It would thus seem that U.S. educators, qua stewards of the public resource that is education, bear a duty to intervene in this situation in ways that foster the collective understanding and self-government that I am suggesting education offers the American people.

III

There are reasons to be optimistic about the possibility of such intervention. Research going back over three decades suggests that Americans share more political commitments than they realize, and that it is the vocal minorities in the wings that are driving the sense of a division. Summarizing a recent study and the associated background literature, Stevens (2019) writes (emphasis in the original):

- Democrats and Republicans significantly overestimate how many people on the ‘other side’ hold extreme views. Typically, their estimates are roughly double the actual numbers for a given issue.

- Greater partisanship is associated with holding more exaggerated views of one’s political opponents.

- The Perception Gap is strongest on both “Wings” (America’s more politically partisan groups).

- Consumption of most forms of media, including talk radio, newspapers, social media, and local news, is associated with a wider Perception Gap.

- Education seems to increase, rather than mitigate, the Perception Gap (just as increased education has found to track with increased ideological prejudice). College education results in an especially distorted view of Republicans among liberals in particular.

- The wider people’s Perception Gap, the more likely they are to attribute negative personal qualities (like ‘hateful’ or ‘brainwashed’) to their political opponents.

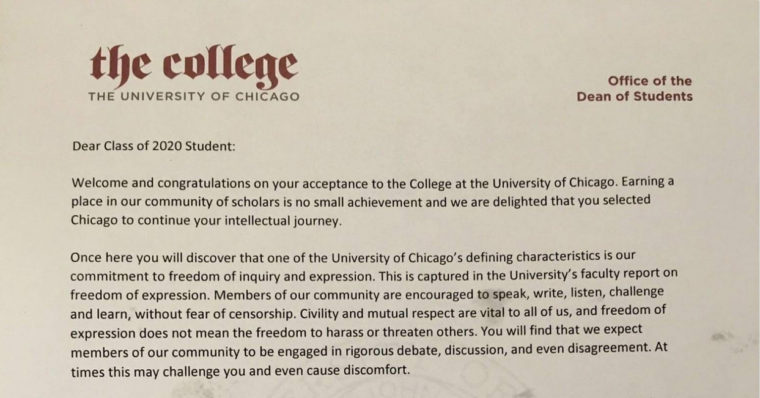

My proposal in this essay is that educators make an effort to speak to the middle on politically-charged issues, and toward that end I gather together some social-scientific data and offer an interpretive gloss about how to proceed. My focus will lie on the situation on college campuses, as I believe that university educators have a particular duty to model the norms of thoughtful conversation that are needed for the development of mutual understanding. Higher education in the U.S. today has seen its own trends of increased political polarization, however, and so it will be important for the academician to address the problem as it appears within the academy as well. But if we educators can build up a bulwark of sensible people in the middle of the debate on university campuses, we might hope to more effectively intervene in the situation with the public at large.