| By Sergia Hay |

I’d like to thank Shane Courtland for his reply to my response to his original posting, “Faith and Betrayal of the Philosophical Method.” I’m eager to continue this conversation about an important and timely subject: free speech in the classroom, and perhaps more broadly within public discourse. As such, it is also connected to other current debates about the appropriateness of trigger warnings, perceived over-sensitivity of some students and fellow citizens, explicit and implicit censorship, and political correctness. (Editor’s note: Check out SOPHIA’s online symposium on trigger warnings here!).

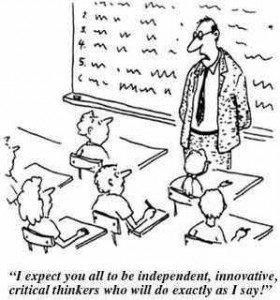

At the end of his reply, Courtland wrote, “It is for the sake of progress, not in spite of it, therefore, that I champion first and foremost the philosophical method over and above any particular view that has come from it.” I agree that philosophical method should be used as a means for progress, but I don’t believe the method itself is value-free or neutral. On the contrary, I think that philosophical method and the subjects we choose to examine with the method are already biased, even if for good reason.

Most of us who teach philosophy, I would venture to guess, have adopted classroom discussion guidelines that are similar to the ones described by Courtland. Most of us, I trust, have been trained to emphasize the role of reasoning over opining in the construction of arguments, to temporarily suspend judgment to weigh evidence, and to have a basic requirement of civility. I do this because I share John Stuart Mill’s optimistic attitude that “wrong opinions and practices gradually yield to fact and argument.” Also like Mill, I don’t believe that the argumentative methods of philosophy alone can prompt us to revise our erroneous thinking, but rather “discussion and experience” and further discussion “to show how experience is to be interpreted” are all added together in a complex recipe of genuine and lasting persuasion. Argumentation is but one ingredient along with human relationships, values, identities, our historical circumstances and systems, and our understanding of these things.

The central and difficult issue Courtland presents in his response to me has to do with our freedom and responsibility to examine all views. The position Courtland presents, via Mill, is two-fold: 1) if someone holds the correct view and it goes unchallenged, then the view is in danger of becoming dead dogma, and 2) if someone holds the wrong view and it goes unchallenged, then the view cannot be revised. I am certainly not opposed to challenging views, since I agree that is the business of philosophy. However, I am opposed to challenging views just for the sake of challenging them alone without the exercise of proper judgment and an understanding of people and their intentions for participating in discussion in the first place.